Happy Birthday, Peter and Jane. 40 this year!

(I wrote this in 2004)

If you want to buy vintage copies of the Peter and Jane books, this isn’t the right page. Try here instead

If you are looking for spoof Ladybird books, rather than the real thing, skip right to the bottom of this page.

And that’s just the books. The ‘childen’ will, of course, be even older since they were meant to be between 5 and 10 years old when they were created, in 1964. This will be a worrying thought for most of us Brits aged between 30 and 45 (and a good many younger) who will remember Peter and Jane as childhood aquaintances who where charged with the task of teaching us to read.

Based on Head teacher William Murray’s system of teaching reading using key phrases and words, apparently over 80 million of us have learnt to read with them. And some of the books are still in print; I still see them for sale in my local bookshop.

The Key Words scheme is based on a recognition of the fact that just 12 words make up one quarter of all the English words we read and write in everyday life and that 100 words make up a half of those we use in a normal day. Teach children these key words first, and they are well on the way to making some sense of most texts.

So, step by step, page by page, these words are introduced and repeated (one might say hammered) to reinforce them as the length and difficulty of the texts increase.

This is reassuring and confidence building for the young reader – but doesn’t make for punchy prose or dynamic dialogue. Here’s an example of chit chat in the P & J household.

The first books were issued in 1964. Ladybird employed a number of different artists to bring to life Murray’s text: Harry Wingfield, Martin Aitchison, Frank Hampson, Robert Ayton and John Berry. These artists all had very different painting styles (Aitchison and Frank Hampson had previously workd on the classic comics The Eagle and The Marvel) but the brief was to produce appealing, naturalistic artwork and obviously the main characters, Peter and Jane, had to be recognisable throughout.

The first models for Peter and Jane were, I believe, Jill Ashurst and her friend Christopher Edwards who lived near Wingfield in Sutton Coldfield and who were only 4 or 5 years old at the time. Subsequent artists used their own models, adapting the pictures for the sake of consistency. This is why Peter and Jane in the 1960s books seem to have only one main outfit each – a white frock and yellow cardie for Jane and shorts and red jumper for Peter.

Different Versions

So far I’ve been referring to these books as thought there were only one versions – the 1960s version. However, in 1970, only 6 years after first publication, Ladybird decided that the books needed some up-dating.

This, I think, is one of the most interesting aspects of this series, because you can immediately see the point. The softly luminous, idealised pictures of Peter and Jane’s home life and activities have their roots firmly in the 1950s and before.

I wonder if the original target audinece were aware of the nostalgic, retrospective feel to them when they first came out? Perhaps there was an awareness even then that these idylic domestic tableaux were unreal and presented a world that had never existed. (Yes, I was part of that early audience, but at the age of 5, I don’t think my powers of analysis were up to the job). Or is it that those years, between the mid-sixties and early seventies saw exceptionally dramatic social change for families. Is this dramatic period of change encapsulated by the 2 versions of the books?

Because if you flip through the pages of a 1970s revised edition, it will still feel pretty modern today – which the first version absolutely does not – although produced nearly 35 years ago. No mobile phones, designer trainers or computer games – but the children have scruffy hair, wear jeans and T-shirt and don’t tidy up after themselves.

It is hard to imagine the Mummy and Daddy of the mid-60s artwork on even speaking terms with their 70s equivalents. Instead, Mummy and Daddy senior would have far more in common with the Mummy and Daddy of the 1940s and 1950s stories such as Mick the Disobedient Puppy,or Shopping With Mother. The Mummies would have got together to discuss knitting patterns while the Daddies smoked their pipes and discussed world affairs.

Here are a couple of 1950s Ladybird families – from the 497 Animal series stories – Tiptoes the Mischievous Kitten (1949) and Mick the Disobedient Puppy (1952). Now they would be perfectly at home with Peter and Jane’s mid-60s Mummy and Daddy. I’m sure they would have shared an understanding of the importance of gender roles and a good bed-time routine.

They would have understood the importance of leaving Daddy to rest and catch on on his reading after a hard day in the office.

But what would they have made of these scenes painted just a few short years later in the early 70s equivalent pictures? Daddy doing the washing up? Mummy busy with her own affairs? Peter’s elbows on the table? Jane just helping herself to milk from the fridge? and even the cat misbehaving?

Which version should I collect?

The good news is, if you want to acquire a set of these books to help a child to read, it doesn’t matter which version you get – just go for the cheapest. The text is just about the same throughout the versions. It is only the artwork, layout and design that change.If you want to collect a particular version or all the different versions, then read the section below: ‘How can I tell the difference between the different versions?’.

Peter and Jane and social history: Why were the books revised?

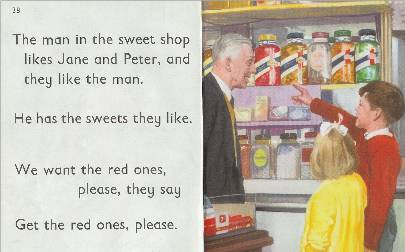

As already discussed, the books were revised in the 70s to give them a more modern look. But it seems likely that the artists were also asked to make changes to reflect perceived shifts in attitudes. So it is interesting to look through the original and revised versions of the books to try to understand what it was about the 1960s books that was deemed unacceptable in the 1970s.The first thing you notice is that Jane gets to wear jeans and is seen playing with roller-skates where once she played with dolls. The scenes portrayed look less ordered and serene. Play time is messier and the children appear to bicker more. However, if, like me, you are happy to spend a few evenings browsing through the two different versions, you’ll find that the biggest changes in the first few books are all to do with sweet consumption. Whereas the Peter and Jane of the 1960s would visit the sweet shop, the 1970s Peter and Jane go to buy apples instead. This change was considered so important that even Murray’s text (so carefully worded and so rarely tampered with) was adapted in the revised books. adapted to reflect the apple over the jelly-baby.

Peter and Jane (and Pat the dog) in a sweet shop, complete with glass bottles and kindly old shop keeper.

And suddenly it has become a green-grocer’s (who has lost the collar and tie but is resplendant with quiff and impressive sideburns) and the children have transferred their enthusiasm to apples. (Did children do that in the 70s?)

Some changes are fairly subtle: Here are the two shop windows of the 60s and 70s versions. Spot the difference.

Apart from the disappearance of the ‘Hornby’? train sets, you might notice that the golly, on the top row of the 1960s book, has been airbrushed out in the 1970s version.

And Daddy was expected to play more of a role in Peter and Jane’s affairs. Whereas in the 1960s version he might watch with detached indulgence the scenes involving Mummy and the children, in the 1970s version he participtes more actively. Here you can see the old Daddy looking on and the new Daddy helping out. Don’t strain yourself Daddy!

How can I tell the difference between the different versions?

(Skip this bit if you don’t plan to collect the books) Basically there are 3 sets of books to collect:

- The original 1960s version

- The early 70s revised version – not all the books were revised at this time.

- The late 70s when all the books were re-packaged and the remaining titles had their artwork revised.

Here’s a picture of the 3 main groups.

The first column shows the original 1960s version. The second column shows the first revision books produced in the early 70s and the last column shows the late 70s books, when the remaining artwork was given a makeover and the layout of the covers was changed to give the framed picure on the front. The revised books kept the colour distinction to show a,b or c books although the colour red became orange).

I have managed to make a mistake in laying the books out for this photo. In the 1B row I have switched over the original version and the ‘first revision’ version. Tut tut. (I should also mention that book 2b is a bit of an anomaly to my neat classification. It has the front cover to classify it as a ‘First Revision’ book, but inside it has the split layout design of the late 70s books and must have been produced on the cusp of the revision period). Since then the 3rd version has been tinkered with; the boards were issued with a laminated finish from about 1983 and recent years have seen other cosmetic changes to the covers – for example to incorporate the spotty strip on the spine that was a feature of Ladybird books from the end of the 1990s. But to this day the contents remains much the same as it was in 1979.

There were other smaller cosmetic changes that some collectors set store by:

For example, originally the key-word symbol was a white key towards the bottom left of the books. Some time in the late 60s, before the first revision, this key was drawn in a black box and moved to the bottom left of the cover – so you can date your books more precisely using such clues. But since these small cosmetic changes have nothing to do with artwork or contents change, I can’t get excited about them and don’t see them as a separate versions of the books.

So… to collect all books from these 3 versions you will need to find:

- All 36 titles from the 1960s

- 11 titles from the early 70s (1a,b,c;2a,b;3a,b,c;4b,5a and 8a)

- All 36 titles from the late 70s.

(My thanks to my friend Paul Crampton for helping me sort this out).

Peter, Jane and John Major’s England

Or – Here come two white, middle-class, gender-divided, politically unreconstructed prigs.

Peter and Jane, (or should I say ‘Jane and Peter’) have had a pretty hard time of it in recent years. Despite all the efforts of the 1970s revision to adjust the stereotyping, add in the odd black face to the background crowd, put Jane in jeans, give Daddy a tea-towel, airbrush out the golly and substitute sweets for fruit – these two non-existant children (remembered fondly by some; hated by others) are often seen as a byword for all that is staid and prim and WASPish.

But in her Telegraph Magazine article of a couple of years ago, Cressida Connolly makes a point that is easily forgotten. She describes these books as ‘radical’- which may initally seem an unlikely choice of adjective. These books were, she states,

“an antidote to the privileged country children of popular literature, such as Swallows and Amazons or the Famous Five. Ladybird children didn’t go to boarding school; they went to the local newsagent’s on their bicycles. The childhood of Ladybirds was egalitarian and unsnobbish, depicting suburbia as the kind of utopia that town planners always intended it to be.”

And just to prove that the sun didn’t always shine in Peter and Jane’s world: let me finish with a picture:

Now, if after all this you actually were looking for the spoof Ladybird books that have been published in recent years, you’re on the wrong website – but let me help you out.

You can buy Miriam Elia’s ‘Dung Beetle’ spoof Ladybird books here.

You can buy Hazeley and Morris’s pastiche Ladybird books here.

You can read my take on Ladybird, spoof and pastiche here.

If you want to buy vintage copies of the Peter and Jane books, this isn’t the right page. Try here instead